How to make it in Hollywood 2020

Is Imagine’s screenwriting accelerator, Impact, the new blueprint for breaking into entertainment as a writer? One aspirant’s journey through the Y Combinator for Hollywood.

For aspiring writers outside of Hollywood’s walled garden, the multi-billion-dollar streaming video arms race can look downright Dickensian.

Tech giants such as Netflix and AT&T are throwing nine-figure contracts at celebrity showrunners including Ryan Murphy, Shonda Rhimes, and J.J. Abrams. Meanwhile, a lucky few get plucked from obscurity, such as Insecure creator Issa Rae or High Maintenance‘s Ben Sinclair. Once you’re recognized as an up-and-coming talent, like Lena Waithe, the opportunities and money are practically limitless.

But even in the era of Peak TV, getting in the door of the dream factory can be daunting. Los Angeles has become prohibitively expensive, and a lot of the jobs that can help you to break into the industry as a writer are low- or no-pay internships or working on branded content. If you’re a writer starting from absolute scratch—with no connections in the industry and no experience writing in film or TV—even setting foot on Peak TV is challenging, if not impossible.

So in an entertainment economy evolving around titanic mergers, mega-deals, billion-dollar IP and content plays, where will a new generation of fresh voices emerge?

It’s a question that Ron Howard and Brian Grazer’s production company, Imagine Entertainment, is trying to answer. Impact is its eight-week accelerator program for screenwriters, which launched earlier in 2019 and recently completed its third batch. Modeled after the startup accelerator Y Combinator, Impact hopes to do for Hollywood writers what YC has done for computer engineers: Create a new avenue for outsiders with a great idea to enter what’s otherwise been a very insular business. Y Combinator boasts that its top alumni, out of more than 2,000 companies that have gone through the program, are collectively valued at $155 billion. Notable successes include Airbnb, Reddit, Stripe, Dropbox, Cruise, and Coinbase.

“It’s so hard to break into the industry, especially if you’re a writer,” says Tyler Mitchell, who runs Impact. “We want to democratize access to the industry for everybody.”

Imagine’s program follows Y Combinator’s rather closely. YC helps founders develop their startup ideas through mentorship and access to resources and an initial seed investment of $150,000 for 7% of the company. At the end of three months, entrepreneurs have the opportunity to pitch their companies to potential investors. Imagine offers its creators a stipend of up to $40,000 and recoups its costs from an undisclosed percentage of a script’s or pilot’s sale, as well as fees on the back end should the project get made. Much as YC entrants have an adviser, Impact pairs each writer or writing group with a shaper—i.e., a working writer who acts as a mentor through the program—who helps them polish their scripts. Woven throughout the program is a speaker series featuring a rotating cast of industry professionals, from entertainment lawyers to J.J. Abrams, akin to YC’s weekly dinners featuring notable entrepreneurs and investors. All roads lead to pitch day (like YC’s Demo Day), where the Impact creators, as they’re called, pitch their pilot or feature in a room of network, film, and streaming executives. Best-case scenario, a creator walks away from pitch day with a sold show or script. But at the bare minimum, they have a thoroughly workshopped project they can take into the world—not to mention a community of shapers and Imagine alumni, so far totaling 72, with whom they can network. Mitchell likens the deal to an executive producing credit, in that Imagine will profit from a successful show or movie coming from its roster, but the creators own their content.

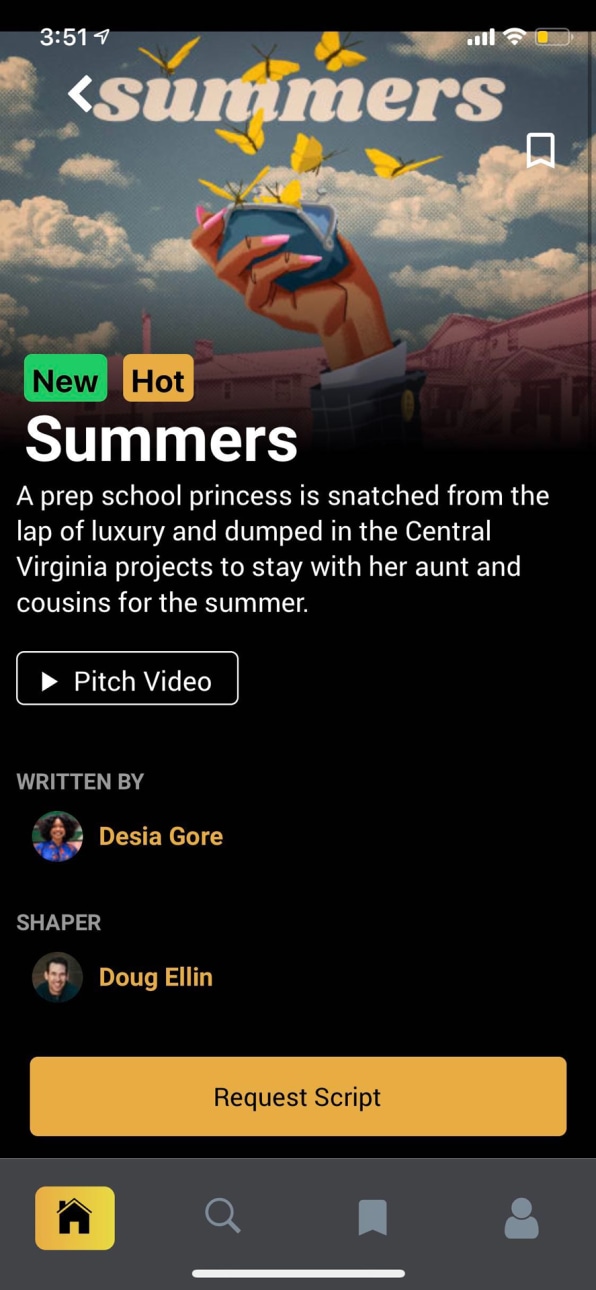

In addition to the program itself, Impact recently launched an app as a one-stop shop for producers and executives looking for the next big thing. Currently used by more than 250 companies—including Netflix, Amazon, Apple, and, of course, Imagine—the app enables its users to scroll through scripts from creators who make it into Impact as well as finalists, watch their pitch-day presentations, make connections directly, and so forth.

Fast Company tracked one of Impact’s 20 creators through the third batch, which concluded last month, to gain a deeper insight into the program.

Because what Imagine is building out with Impact has the potential not only to launch a new writer’s career but even to reshape the entertainment industry as a whole.

Act I: The rookie

“I’ve always loved to tell stories,” says Desia Gore. “It’s always been the way that I understand the world and the way in which I receive understanding back.”

Hailing from Richmond, Virginia, Gore, 25, studied public relations and journalism at George Mason University in Fairfax. But, as she confesses, it was a front for her real passion.

“When parents are paying for school, you’re like, ‘Let me do the thing that has definite jobs after school! I would kind of cheat by taking creative writing classes,” says Gore. “By the end of college, it was like, okay, Desia, you know what you love.”

Before and during college, Gore mainly wrote short stories, mainly about misunderstood girls—a topic close to her heart. There was one story, though, that she kept hitting a wall with. When she started toying around with screenwriting, though, something clicked. So after graduating college in 2017, Gore made the move to Los Angeles.

There’s no shortage of fellowships and workshops for TV and film writers looking to pinpoint their “thing.” When Gore wasn’t waiting tables at Macaroni Grill (where she would turn customers into potential characters in her head), Gore was compiling a list of what seemed like the most promising programs. Through the mentorship initiative of Hillman Grad Productions, Lena Waithe’s production company, Gore came across Imagine Entertainment’s Impact accelerator.

“Anytime you apply to a program you want to look at the alumni, and I was kind of terrified in applying because of the fact that everyone’s credentials seem to be up there,” Gore says. “I went ahead and applied because the application process alone is so good for any writer to do. It was like a pregame to what having a shaper in the program would be like. It really lets you know, do I have an idea here or do I have a story?”

The application for Imagine Impact includes 70 questions aimed at figuring out who the audience is for a show, how it compares to what’s in the market, why this story needs to be told—and why that writer is the one to tell it. Completed applications are disseminated to Impact’s global reader network, a group of more than 100 readers across five countries who have passed Impact’s qualification exam. Impact also evaluates the strength of each application algorithmically.

“For people who have experience in the industry, they might have experience being a staff writer on a show, but they want to create their own show,” Mitchell says. “And for people like Desia, it’s raw talent and voice and drive [that gets them into the program]. And while she doesn’t necessarily come in knowing how to break a half-hour television show, that can be taught. We’re looking for people who have stories bursting from their souls.”

Gore’s batch mates would include writers who’ve previously worked on Netflix shows, developed programming for Disney, and even sold a script to Paramount.

“Your odds of getting in are kind of astronomical,” says Jill Chamberlain, a screenwriting expert and consultant, who generally praises Impact for not requiring a submission fee, paying writers a stipend, and giving them access to some of Hollywood’s finest. “And with Impact, it doesn’t sound like they’re reading the vast majorities of the script. I don’t think those 70 questions are as useful or relevant as reading a script would be. So it feels almost like a lottery.” Impact claims that all applications are read by a human reader.

Act II: The shaper

That said, someone has to win the lottery at some point—and Gore had a winning ticket with her background, personality, and, of course, her pilot idea: a half-hour comedy she refers to as a reverse Fresh Prince of Bel-Air. Based in her hometown of Richmond, Summers tells the story of Tatiana, a 15-year-old rich girl who’s forced to live in the hood with her cousins after her father is arrested and their assets are seized. Gore loosely based the pilot on her own life. When her two sisters wouldn’t stop teasing her that she was too much of a softy, their dad sent her to summer camp in the hood to help push Desia out of her bubble.

What was at first jarring became a personal and creative awakening for her.

“I want to show an area that, usually when it’s shown, it’s a story of trauma and sadness, which is the hood,” Gore says. “But there’s also a lot of community.”

Tasked with helping to develop Gore’s concept was her shaper, Entourage creator Doug Ellin. Shapers choose who they want to work with based on applications, and it’s apparent that Ellin, who also served as an adviser in each of the first two cycles, was looking for a challenge with Gore. Unlike the previous creators he worked with, Gore came into the program with just an idea.

“So you’re flying a little blind,” Ellin says. “And Desia’s a real young writer. She’d only written one screenplay before. But you see [her application] video and you read her short stories, and her voice really came out.”

On the flip side, Gore had some concerns about Ellin that were skin deep.

“One thing I loved is that there’s no elephant in the room with Doug,” Gore says. “It’s very clear that I am black and you are white and there are some things that you’re not going to get. And he’s very respectful of that.”

The focus was on building out the characters and finding the right tone. Even though Gore calls Summers the reverse Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, that wasn’t the tone she was going for. With Ellin’s help, they pinpointed the vibe of the show to be more in line with comedian Bernie Mac’s 2000s sitcom The Bernie Mac Show.

“I said to her at the beginning: At the end of the day, a story is a story,” Ellin says. “But I’m not going to try to step into your lane.”

Ellin also helped Gore restructure the scope of what she wanted to include versus what’s actually relevant to the story.

“It would be something like, is this aspect of the black experience crucial to the story or is it just a thing that you want to see on TV?” Gore says. “For me as a black woman, I know that I have obligations. There are certain things that black people are tired of seeing, and there are certain things that we would like to see. And so when you get the opportunity, of course you want to do everything.”

“But it’s helped me to have Doug as a shaper, to calm me down and say that I am a black woman, so naturally the perspective that I get is going to be from a black woman,” Gore continues. “The plight that comes with that. The lingo that comes with that. They are organically going to come through without me thinking about what black people want and what do they need to see.”

There was, in fact, something pretty major that didn’t make sense to Ellin.

And four weeks into the program—halfway to pitch day—Ellin and Gore tore her pilot apart.

Act III: The twist

“I don’t want to say I’m not somebody that fails per se, but pressure is really interesting to me,” Gore says. “And this program was described to me as a crash course.”

Ellin felt that Gore’s characters weren’t strong enough. In comedies, where everyone’s personalities are dialed up, Gore’s main characters weren’t pushing through like they needed to.

“With half-hour comedy, the characters have to be so incredibly strong in order to carry the show,” Gore says. “You can understand the world. You can understand what’s going to happen—the tone, the time, everything. But if your characters cannot keep the plot moving, then it’s just not going to work out.”

As Ellin put it to Gore, with ensemble comedies such as Golden Girls, Entourage, or Living Single, you can throw out a line and someone would be able to know exactly which character said it.

“Their characters are so solid, you can throw them in any situation and they’re going to react the same in every situation,” Gore says. “So it really doesn’t matter too much what situation they find themselves in. It’s more about them bringing themselves to all of the shenanigans and misadventures they find themselves in.”

Gore’s challenge wasn’t just to solidify characters. With her lead protagonist, Tatiana, she had to pull a full 180.

In her script’s fish-out-of-water story, Gore initially had Tatiana act like a stuck-up brat who makes it clear at every turn that she doesn’t belong in her cousin’s world. But that wasn’t working for Gore. Part of why she wanted to tell this story was to showcase a place like Richmond that doesn’t see much representation on TV and get audiences to see it how she saw it growing up: as a fun, vibrant, and creative environment.

“What I decided would be better is if she was someone who is blindly optimistic. She’s always finding the silver lining where there is no silver lining. She’s trim, and she’s a neat freak. She has dreams of being a really dignified woman like the U.S. Secretary of Education,” Gore says. “So her problem is she doesn’t really understand the reason why she’s been able to be so jolly is because she hasn’t had to face a lot of the problems most people faced.”

“Screenwriting is a tricky thing,” Ellin says. “My first script that I wrote that I thought was so good, I remember handing it out to people and they were like, ‘What the hell is?’ So I know the process of going, ‘Wow, I’ve watched movies my whole life. How come I can’t just sit down and write a story that actually makes any semblance of sense?'”

At the same time that Gore was rebuilding her characters, she also had to start thinking about how she was going to sell her story to an audience.

On pitch day, creators have up to 10 minutes to sell their idea to an audience of producers and executives. For half-hour comedies like Gore’s, Ellin pushed her not to waste a single minute.

“The main thing he emphasized is your pitch has to be funny,” Gore says. “Every single line has to be funny.”

Act IV: The pitch

“I love this young lady.”

It’s finally pitch day, and Ellin warmed up the crowd with a brief introduction. “Her energy, her vibe—and her idea is simple and sellable, but her voice is very unique. This is only the second screenplay she’s ever written. So I’m really excited for her future, and you guys are going to love her.”

Gore took to the stage with a cheeky effervescence and a stack of note cards she didn’t look at once. The work that she and Ellin had put into making every second of her pitch count paid off: All of her laugh lines landed with the crowd.

“So my story Summers is actually set in my hometown of Richmond for a few very valid reasons,” she opened. “The first one being I feel obliged to represent at all times. Two, Virginians do not get a lot of camera time. And three, the world deserves to see how weird we are! Cameras never come to Virginia unless we’re talking Monticello or Jamestown or dead white presidents. And that is not on my program today.”

It was a real-life sink-or-swim scenario for her that, years later, she reframed as the catalyst for her pilot.

And those supporting characters that needed to have more punch on the page? Gore got them exactly where they needed to be with brief descriptions that painted an instant and precise picture: “Aunt Clementine is a 40-year-old widow with [Sister, Sister matriarch] Lisa Landry’s enthusiasm, but Clair Huxtable’s tolerance for disrespect. Her oldest daughter Tangie is a 17-year-old rebel. She relieves her anger by screaming bars into mic and flicking niggas off like lights. You know, a real sweetheart. Mango is 15 years old. She drinks water. She minds her business. She plays basketball. She fixes the broken appliances around the house using paper clips and rubber bands—you know, just some nigga-riggin’ things to save some bread and keep the peace.”

“My goal as a creator is not just to create but to relate,” Gore said in closing. “So make an audience reminisce, feel, and laugh. And shit, we,”—here she made an obvious gesture to the back of her hand signaling the “we” as black folks—”sho’ nuff deserve to.”

In short: Gore killed it. Love her, they did.

“The minute I got off the stage, people were running up to me to introduce themselves,” she says. “I couldn’t’ve begged God for a better outcome.”

A month after the program ended, Gore has met with four management companies and is figuring out who she wants to sign with. That team will then follow up with 50-plus executives who are currently reading her script through the Impact app.

Given the fact that Impact isn’t even a year old yet (and that TV and film projects can take years to come to fruition), it’s hard to measure how successful pitch day has been. Of course, getting your script sold is a victory in itself, and that has certainly happened through Impact. One of the program’s most notable success stories has been Godwin Jabangwe, a cycle-one alum who, after coming to L.A. for Impact with little more than $30 in his pocket and a copy of To Kill a Mockingbird (“The airline lost his suitcase,” Mitchell recalls), managed to sell his animated musical about the Shona people of his country in a four-way bidding war to Netflix for a mid-six-figure sum. Philip Tarl Denson, an Australian physics teacher, sold his TV pilot Anomaly to Legendary in a three-way bidding war.

“We know that we’re finding incredibly talented people. But, on top of that, does our 8-week boot camp work? Can you actually go from an idea to a screenplay that is ready to go to market and sell in eight weeks? Yes, we’ve proven that,” Mitchell says. “We hope the app will grow and become a real platform, sort of like a LinkedIn for the global media market, that will be able to create those connections between people and hopefully lead to quicker outcomes of projects being actualized.”

As for Gore, her dream of making it in L.A. as a screenwriter is all but actualized.

“I’m just so grateful to Imagine for respecting your voice and not wanting to change you or package your personality, but wanting to make you the best version of yourself,” she says. “I want to keep that in mind when I’m stepping out into these meetings. I was treated so well and with so much respect in this program that I know what to look for wherever I go next.”

"make" - Google News

December 17, 2019 at 07:00PM

https://ift.tt/2S0pTCz

How to make it in Hollywood in 2020 - Fast Company

"make" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2WG7dIG

Shoes Man Tutorial

Pos News Update

Meme Update

Korean Entertainment News

Japan News Update

No comments:

Post a Comment